I am looking at the record cover of Paul Quinn’s The Phantoms and the Archetypes, released in 1993 by the influential label Postcard. It shows the singer sitting pensively, a cigarette in his hand. The photo is solarized, crudely cut out and pasted on a black background. His face and hands are washed out by a beautiful incandescent-neon blue light. He’s like an apparition. The white silhouette has very little detail and the shadowy grain on his shoulder has some speckles of magenta dust, which let you know that the source photograph used for the cover was a cheap color photocopy. The effect is striking; it’s almost painful to stare at and conjures perfectly what’s to come when the album is played, a séance of cinematic sophistication and Velvet-inspired roughness, mediated by Paul Quinn’s voluptuous and sorrowful voice.

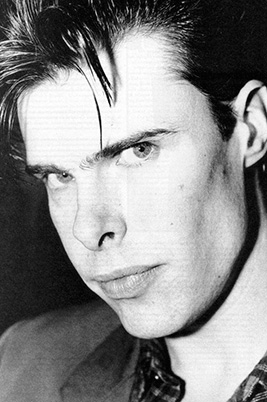

The son of a Pentecostal pastor, Paul Quinn grew up in Dundee, a Scottish city near the North Sea in a household where pop music was banned. “We lived behind the church. The only tolerated music was religious hymns from the 18th century. We didn’t have a TV or a record player, just a small wooden transistor. At night I would borrow it and secretly listen to pop music programs.”

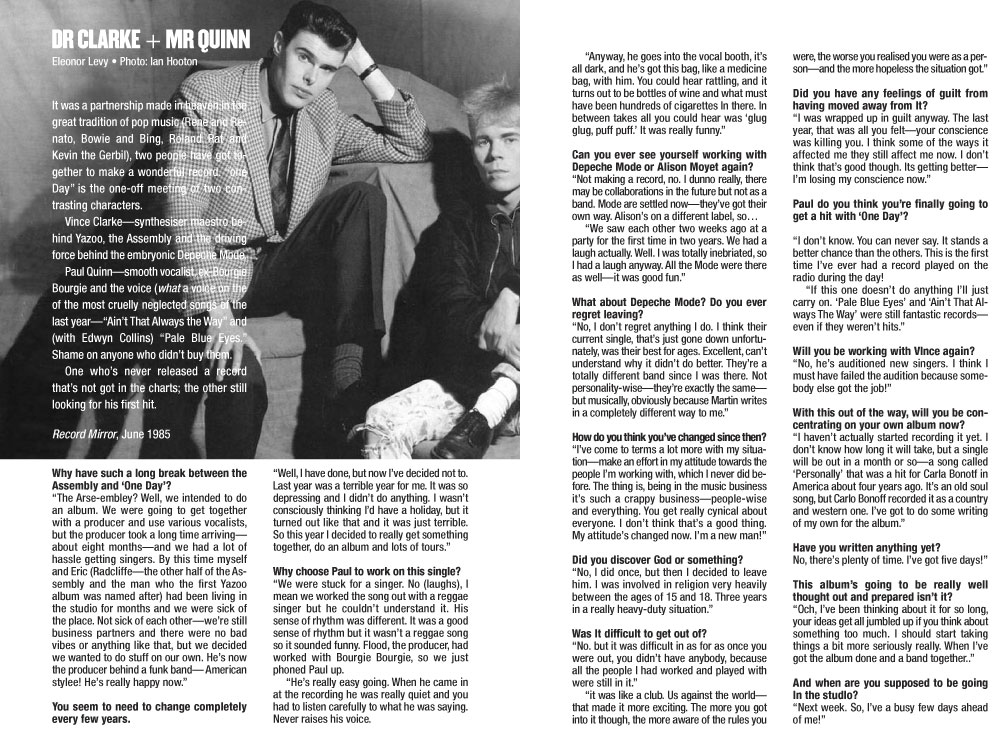

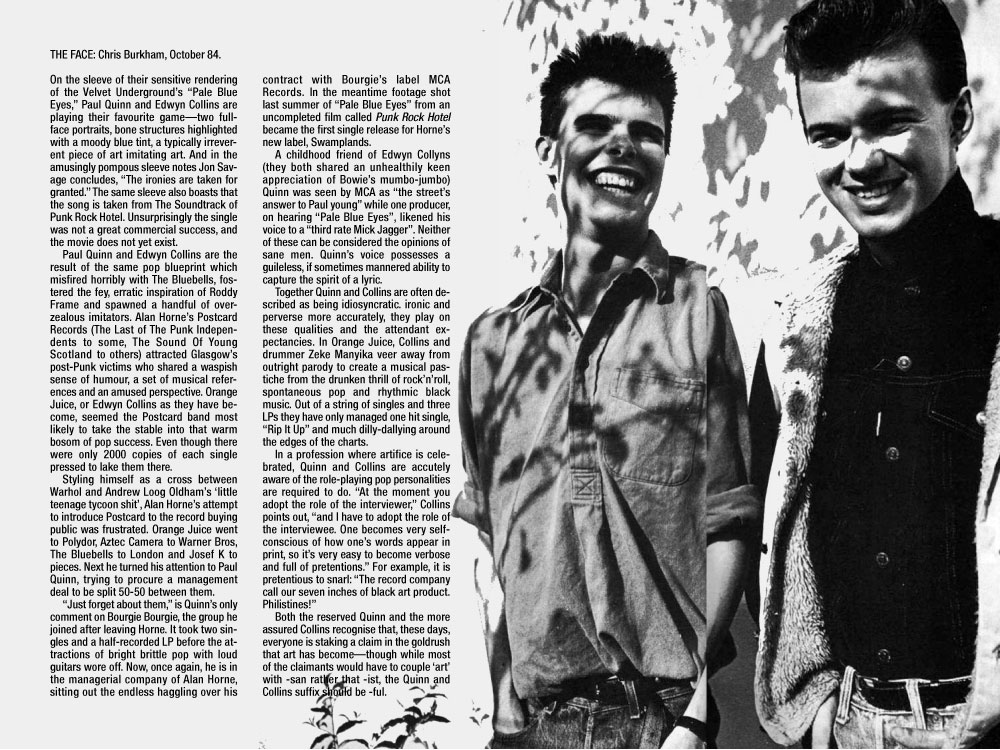

At 11, Quinn was a classmate of Edwyn Collins (of Orange Juice). “I remember I’d just go into school carrying Roxy or Bowie albums under my arm, and he was getting into pop music at the time so he must have thought that I was a like-minded soul. That’s how we became friends. It was rock that brought us together.” When Collins moved to Glascow at age 15, they stayed in touch: “Edwyn used to keep me up to date with what was going on in punk. There were no like-minded people in Dundee. I used to go up to Glasgow to watch Roxy Music and buy smart gear.”

Edwyn Collins was the first to start a band, The Nu-Sonics, the first incarnation of Orange Juice, in 1976. Opening for Steel Pulse in 1978, he met Alan Horne, who founded the label Postcard (The Sound of Young Scotland) two years later to release music from the burgeoning scene. Horne, a gay depressed adolescent, took a trip to Europe at 16 and forced himself to communicate with strangers in an attempt to overcome his debilitating shyness. Horne was obsessed with movies and music, particularly disco, soul, and the Velvet Underground. Bored with punk self-righteousness and lack of humor he developed a vague interest for Reggae music. The Nu-Sonics did two things that night that impressed Horne greatly, “they begin their set with the relatively obscure Velvet Underground’s song We’re Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together (only featured in a live album from 1974) and later a friend brought onstage sung the chorus from Chic’s latest hit.”

Records were made and every Postcard single had to be played against the Velvet’s Pale Blue Eyes.

A friendship started between Horne and Edwyn Collins. The Postcard core group shared the same 4-bedroom apartment in a working-class neighborhood of Glascow. “It’s in this apartment that I truly learned to play music. The atmosphere was amazing. Music was played 24 hours a day. Malcolm Fisher on acid would play his grand piano at 4 AM. … It’s also at that time that we started taking drugs for the first time. The big thing then was speed. Alan brought some back regularly from London,” remembers Paul Quinn.

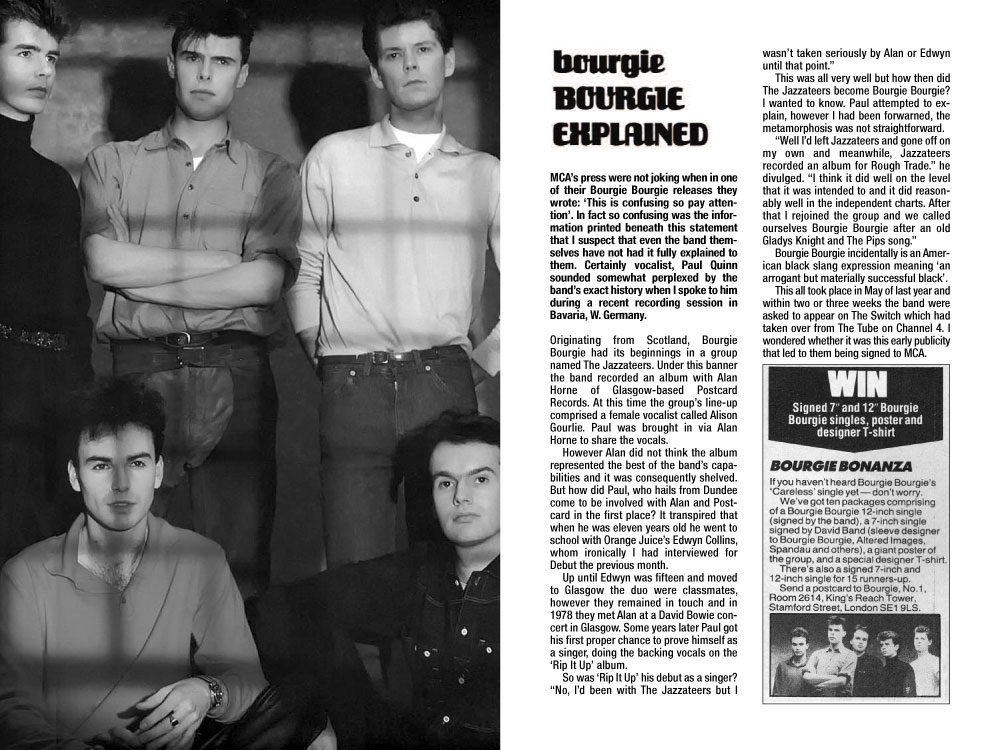

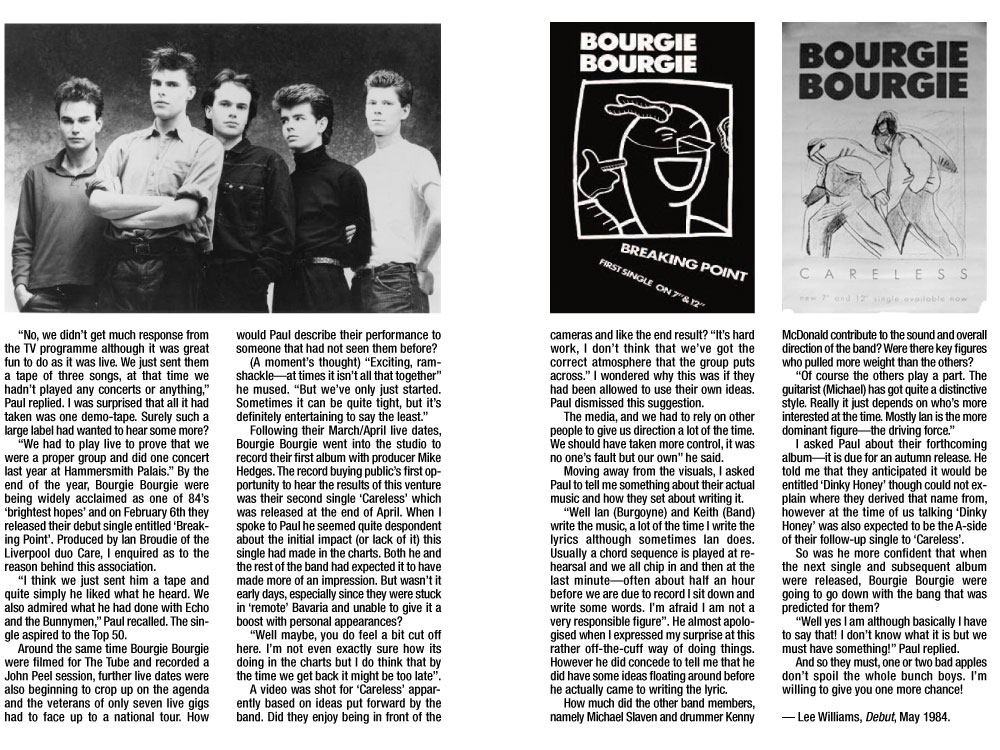

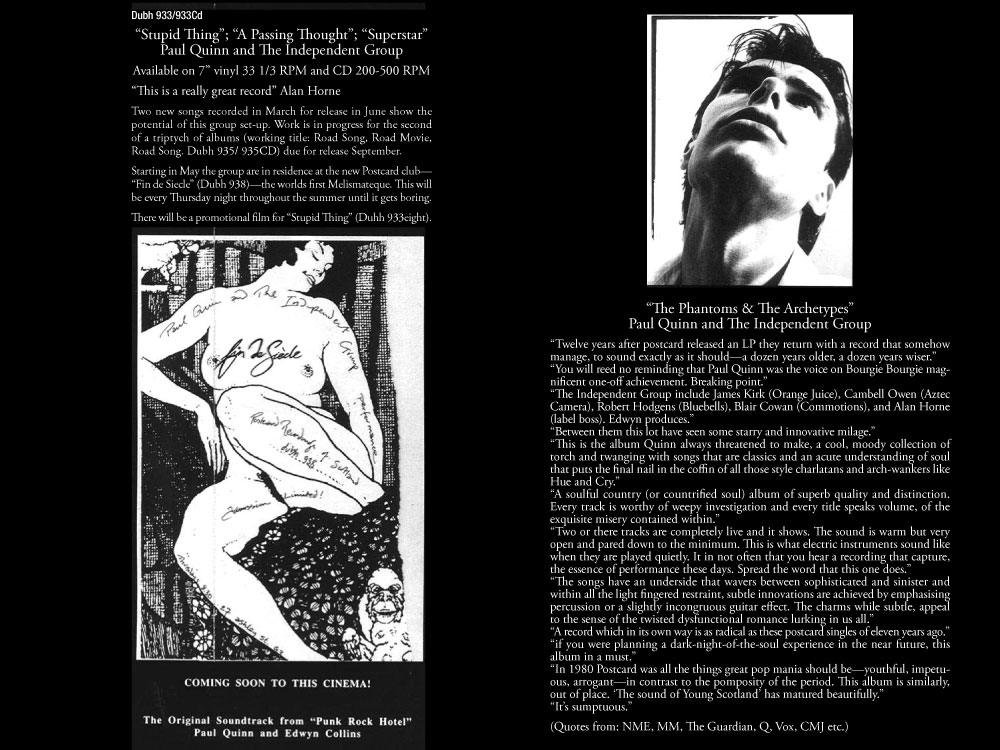

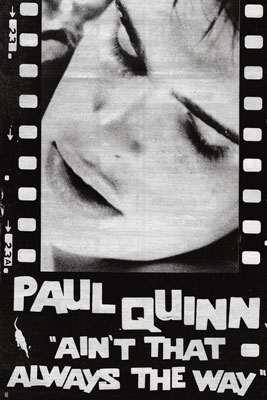

Records were made and every Postcard single had to be played against the Velvet’s Pale Blue Eyes. Horne would then lament tearily that they could never make a record as good as that. Postcard released a handful of singles (Aztec Camera, Go-Beetwens, Josef K) and folded a year later, when Orange Juice signed to the major label Polydor in September 1981. Paul Quinn’s band, Bourgie Bourgie, was picked up by MCA Records. Two singles were released in 1984, Breaking Point and Careless but failed to enter the charts despite the good press the band was getting. Bourgie Bourgie was dropped while recording their debut LP in Bavaria. The same year Quinn signed with Alan Horne’s Swamplands Records, his follow up to Postcard, which was bankrolled by London Records.

The first released single was Paul Quinn and Edwyn Collins cover of the Velvet Underground’s Pale Blue Eyes. The new label was also short-lived and Paul Quinn’s full-length super-8 movie, Punk Rock Hotel never materialized. Very few of Horne ideas—including the “campy, family-oriented trio,” the Savage Family, with new-wave chanteuse Patti Palladin, Warhol transsexual Superstar Jayne County and a live chimpanzee—ever came to fruition or made an impression on the charts. Horne recalls, “I used to go round to Patti Palladin’s and smoke loads of dope. Jayne County would come around looking crazy and she knew I loved hearing stories about Bowie and the Velvets, so she would play up. I would be sitting there stoned, lying on the couch, and she would be performing stories. It was better than any theatre, or rock, or anything.”

His contract with London prohibited Quinn from recording anything for another label, and his career was put on hold for eight years. “I stayed home, played guitar. I decided to be calm and patient. I built for myself a little artificial world.”

Alan Horne resuscitated Postcard in ‘92 to set the record straight and close the book with the aim of releasing both Paul Quinn’s much delayed debut album and a less polished version of Orange Juice’s debut album, which was already recorded but rejected by Polydor. The new incarnation of the label closed after 3 years with an EP called Pregnant with Possibilities, which included Paul Quinn’s last recorded song ever, Tiger, Tiger, a cover of the band Head. According to Edwyn Collins, Horne—who didn’t do promotion and didn’t tour his bands—was disappointed by the lack of interest in the revived Postcard. Paul Quinn had a different take on Horne’s ambition, “the image of Postcard is too beautiful, and there was no desire to capitalize on the nostalgia.”

In Cheap Flight, the handmade zine that accompanied what was to be Quinn and Horne’s ambitious last voyage, the Cowboy Resonating Tour, all the clues are revealed in a procession of influences and excavated excerpts from books and newspaper clippings: McLuhan, Warhol, Brando, Barbara Rush, Ronald Firbank, Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou. The first page starts with the proclamation, “Don’t forget Marcel Duchamp.” Quotes: “Allow us to side-step the collective amnesia that constantly threatens to engulf us.” Titles: “The invention of adolescence,” “Contact and love for sale,” “Loneliness followed me my whole life.” Personal recollec- tions from Horne, “As a teenager Midnight Cowboy really got me. Taxi Driver really got me too. The Wild One/Scorpio Rising/The Loveless—such a perfect triptych.” Nothing seems superfluous. An excerpt from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: from A to B about the nature of beauty becomes a statement of intent for the revival of the label. Warhol talks about how Schrafft’s restaurants were modified to keep up with the fashion of the times and lost their appeal. “If they could have kept their same look and style, and held on through the lean years when they weren’t in style, today they’s be the best thing around.”

The virus of pop culture, the initial rush morphs into a stubborn allegiance to a moment in time when something was activated.

Maybe the most revealing moment in the zine is when Alan Horne tells the quintessential story of ditching school on a Thurs- day afternoon and taking a train to London for a couple of days in 1976 (a 12-hour ride then)… watching movies, shoplifting Bowie singles. “I was 17… all the sex-shops and bizarre records you wouldn’t see anywhere else and xerox ads for the Sex Pistols—some new group I’ve never heard of. It was a good name. You had to remember everything in those days. Your mind was your video so you could get things wrong and they turn out better that way. I could rerun Cracked Actor over and over in my head— all the lines and the clothes… wish I didn’t have to sit through another exam on Monday and I could stay in London. So much stuff down there. You could get yourself lost down there.” This is the point of origin; he exposes the birth of an obsession that can’t be undone. The virus of pop culture, the initial rush morphs into a stubborn allegiance to a moment in time when something was activated. A life spent trying to recapture it endlessly, while knowing that it carries no currency in the present, and that life is elsewhere. “When they said they wanted real life, they meant real movie life!”

Paul Quinn’s records were received enthusiastically by the press: “criminally overlooked,” “a great lost pop voice of the ‘80s,” but failed to connect with an audience. John Mulvey in his review for the NME exposes the problematic the record poses and makes the best case for it: “There is no doubt the whole package is something of a hangover from another time, but when it’s from a time so maverick, exciting, and too often forgotten, and when it gives a talent like Quinn’s a belated showcase, then living in the past can be wholeheartedly forgiven.”